Go is perfect for control planes, but when microseconds count, you need a different strategy. Here is how to migrate router functions to Rust or C without falling into the FFI performance trap, including architecture patterns and Kubernetes deployment strategies.

Go has rightly become the language of choice for cloud-native infrastructure. Its concurrency model (goroutines), robust standard library, and compilation speed make it ideal for building complex networked services.

However, when building a full network router, where you are aiming for 10Gbps, 40Gbps, or even 100Gbps line rates, pure Go implementations often hit a predictable wall. The latency tail gets longer, and throughput jitters under heavy load.

The bottleneck isn’t usually your logic; it’s the runtime. Garbage collection pauses and the Go scheduler’s inherent overhead, while minimal for web services, are catastrophic when your time budget per packet is under 100 nanoseconds.

The natural instinct is to rewrite “hot paths” in C or Rust. But be warned: A naive migration will make your router slower.

This article explores why simple migrations fail, introduces the necessary architectural shift, and justifies the best modern approaches for marrying Go’s ease of use with Rust’s raw speed.

The Trap: The High Cost of Crossing Boundaries

The most common mistake engineers make when optimizing Go routers is rewriting a single, CPU-intensive function (like checksum calculation or header parsing) in Rust and calling it via cgo (Go’s Foreign Function Interface) for every single packet.

The Math of Failure

To process 10Gbps of traffic using standard 64-byte packets, your router must handle roughly 14.88 million packets per second (Mpps). This gives you a budget of roughly 67 nanoseconds to receive, process, and transmit a packet.

Calling a C or Rust function from Go is not free. The cgo mechanism has to save Go stack pointers, switch to the system stack, interact with the Go scheduler to ensure the thread isn’t preempted during the call, and then reverse the process on return.

Benchmarks show the overhead of a single cgo call is typically between 60ns and 150ns, depending on processor architecture and OS scheduling.

If you call a Rust function for every packet, you have already spent your entire processing budget just switching languages. You lose before you even start processing.

The Solution: The Architectural Split

To achieve high performance, we must stop treating C/Rust as mere libraries and start treating them as a separate subsystem. We must adopt the industry-standard pattern of separating the Control Plane from the Data Plane.

- The Control Plane (Go): The “brain.” It handles complex, low-frequency tasks: BGP/OSPF routing protocols, REST/gRPC APIs, configuration management, metrics aggregation, and authentication. Go excels here.

- The Data Plane (Rust/C): The “muscle.” It handles simple, high-frequency tasks: packet lookups, header modification, encapsulation, and forwarding. It must run without GC pauses. Rust excels here due to memory safety without runtime overhead.

Instead of thousands of tiny function calls per second, the Control Plane asynchronously programs the Data Plane via shared memory or highly efficient ring buffers.

The Best Options and Justification

There are two primary paths to achieving this split in modern Linux environments. We choose Rust for the data plane components over C due to its compile-time memory safety guarantees, which are critical in kernel-space or ring-0 networking contexts.

Option 1: Go + eBPF (XDP)

This is currently the preferred approach for cloud-native networking (used by Cilium, Calico, etc.).

How it works: You write the data plane logic in restricted C or Rust that compiles to eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) bytecode. This bytecode is loaded directly into the Linux kernel and attached to the network interface via the XDP (eXpress Data Path) hook. Packets are processed by your custom logic before they even touch the Linux kernel networking stack.

Justification:

- Extreme Performance: By bypasses the kernel’s socket layer, iptables, and conntrack, XDP can handle tens of millions of packets per second.

- Safety: The kernel verifies eBPF code to ensure it cannot crash the system or access illegal memory.

- Seamless Go Integration: Go libraries like

cilium/ebpfmake loading programs and interacting with eBPF “Maps” (shared hash tables for routing rules) trivial.

Option 2: Go Control Plane + DPDK Rust Data Plane

This is the “nuclear option” for appliances, high-frequency trading, or ISP-grade gear requiring 100Gbps+.

How it works: DPDK (Data Plane Development Kit) is a set of libraries that allows a userspace application to take complete control of the network interface card (NIC), bypassing the kernel entirely. You build a standalone Rust application using DPDK bindings, and your Go application communicates with it via shared memory (e.g., unix domain sockets or memif).

Justification:

- Maximum Throughput: It is the absolute fastest way to move packets on commodity hardware. It uses polling drivers instead of interrupt-driven I/O.

- Deterministic Latency: By pinning data plane threads to dedicated CPU cores, you eliminate scheduling jitter almost entirely.

- Complexity: It is significantly more complex. You lose standard Linux networking tools (tcpdump, standard routing tables) and essentially have to rebuild networking functions from scratch in userspace.

Architecture Design: The eBPF Approach

Here is a high-level view of the recommended architecture using Go and eBPF/XDP.

graph TD

subgraph “User Space (Go Control Plane)”

API[gRPC/REST API] –> Controller[Route Controller Logic]

BGP[BGP Daemon] –> Controller

Controller — “Updates Rules via syscall” –> EBPFMap[(eBPF Map\nShared Memory)]

MetricsAgent[Metrics Agent] — “Reads Counters” –> EBPFMap

end

subgraph "Kernel Space (Linux OS)"

EBPFMap -- "Read Routing Table" --> XDPProg[Rust eBPF XDP Program]

NIC[Network Interface Card] -- "Incoming Packet" --> XDPProg

XDPProg -- "Pass (To Kernel Stack)" --> KernelStack[Linux Network Stack]

XDPProg -- "Drop" --> Drop[Discard]

XDPProg -- "Redirect (Fast Forward)" --> NICOut[Network Interface Card]

end- The Go Controller handles BGP peering and API requests. It determines that IP

1.2.3.4should go out interfaceeth1with MAC addressAA:BB:CC.... - Programming the Dataplane: The Go Controller writes this rule into an eBPF Map. This is a highly efficient key-value store located in kernel memory.

- The Packet Arrives: The NIC receives a packet. Before the kernel allocates an

sk_buff(which is expensive), the XDP Program (written in Rust) is triggered. - Instant Decision: The Rust program performs a lookup in the eBPF Map. It finds the match, modifies the Ethernet header for the next hop, and issues an

XDP_REDIRECTcode to send it straight back out the correct NIC. The packet never enters the standard Go runtime.

Kubernetes Deployment Implications

Migrating to these high-performance architectures changes how you deploy your router pod in Kubernetes. You cannot use standard, restricted pods.

1. Privileges and Capabilities (eBPF)

To load eBPF programs into the host kernel, your Go pod needs specific Linux capabilities. You generally don’t need full privileged: true, but you do need:

securityContext:

capabilities:

add:

- CAP_BPF # Required to load eBPF programs

- CAP_NET_ADMIN # Required to attach XDP to interfaces

- CAP_SYS_ADMIN # Sometimes required depending on kernel version/map typesurthermore, because XDP operates on actual physical or emulated host interfaces, your pod usually needs to run in the host network namespace:

hostNetwork: true2. DPDK in Kubernetes (The Hard Way)

Deploying DPDK is significantly harder. Because DPDK needs direct hardware access, you must use:

- SR-IOV: Your physical NIC must support splitting into “Virtual Functions” (VFs).

- DPDK Device Plugin: K8s needs a device plugin to discover these VFs and schedule pods onto nodes that have them available.

- Multus CNI: Standard K8s networking (like Calico or Flannel) provides the

eth0for Kubernetes API traffic. Multus allows you to add a second, high-performance interface to the pod that is passed through directly to your DPDK application.

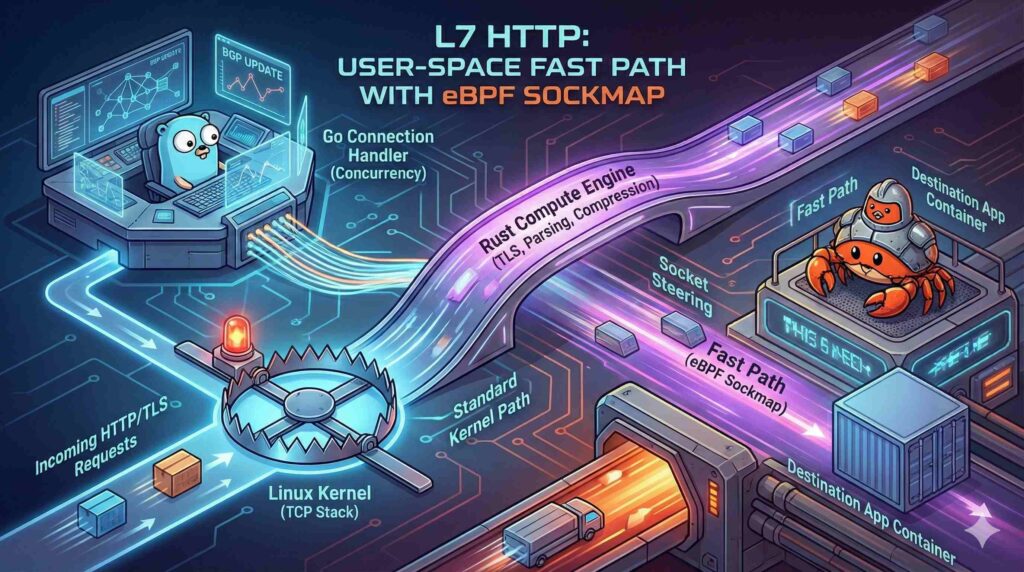

Handling L7 Traffic (HTTP): The User-Space Fast Path

While eBPF and XDP are miraculous for L3/L4 packet routing, the game changes completely when you need to handle HTTP. To route HTTP, you must terminate the TCP connection, reassemble the stream, decrypt TLS, and parse the application headers.

eBPF cannot easily handle this because HTTP payloads are variable-length and require complex state management that exceeds kernel verifier limits. You are forced back into User Space, where the Go Runtime’s Garbage Collector usually becomes the bottleneck.

Here is the high-performance architecture for L7: The Go-Rust Hybrid Proxy.

The Challenge: The “Per-Request” Allocation Storm

In a pure Go router (like one built on net/http), every incoming request generates significant heap allocations (headers, context objects, buffers). At 100k+ requests per second, the GC struggles to keep up, leading to latency spikes (tail latency).

The Solution: Rust for Parsing & Encryption (The “Sidecar” Pattern)

Instead of rewriting the entire web server, keep Go for the concurrency model (handling thousands of connections is what Go is best at), but offload the CPU-heavy portion of the request to Rust via FFI.

Architecture:

- Go (Connection Handler): Accepts the TCP connection and handles the IO wait loops (epoll).

- Rust (Compute Engine):

- TLS Termination: Use Rust bindings (like

rustls) to handle the handshake and encryption. Rust generally offers more predictable performance for crypto operations than Go’s pure implementation under load. - SIMD Parsing: If you are inspecting JSON bodies or complex headers, pass the raw buffer to a Rust function utilizing SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) libraries like

simd-json. - Compression: Offload GZIP/Brotli compression to Rust.

- TLS Termination: Use Rust bindings (like

Optimization: eBPF Sockmap (Socket Steering)

Even in User Space, you can use eBPF to cheat. If your router is acting as a “Sidecar” (receiving traffic and forwarding it to a local application container), you can use an eBPF Sockmap.

Normally, forwarding traffic between two local sockets involves copying data from User Space -> Kernel -> User Space. With a Sockmap, the kernel redirects packets from the receive queue of the router directly to the receive queue of the destination app, bypassing the TCP/IP stack entirely for the local hop.

Revised Kubernetes Design for HTTP:

- Ingress: Standard Load Balancer.

- Router Pod:

- Container A (Go+Rust): Terminates TLS, validates the JWT auth token (using Rust), parses headers.

- Optimization: Uses

bpf_msg_redirect_hashto push data to the application container.

Pro Tip: For HTTP traffic, the CGO overhead (150ns) is negligible compared to the request processing time (microseconds/milliseconds). Unlike packet processing, you generally do not need to batch HTTP requests to see gains from Rust, provided the work being offloaded (like parsing a 10KB JSON body) is significant enough.